Measuring the ANZACs Tutorial 5: Attestations

In our first four tutorials (One, Two, Three, Four) we covered classification, and marking of Death Notifications and History Sheets, including the Statement of Services. Today we move along to the last key document in the files: the attestation (Check out the Field Guide for a shorter synopsis)

We’ve emphasized in previous posts how Measuring the ANZACs is trying to create an efficient index to the documents. We’d love to transcribe everything right now, but it’s more realistic to think we can do some key information that tells us the kind of people we have in the files, who they are, and the types of things that happened to them.

You can think of the three different types of form we’re collecting in this way

- Attestations describe who men were when they arrived in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. It’s a snapshot of their life at the start of their engagement with the war. We call this “cross-sectional” data in our analyses.

- The History Sheet and Statement of Services describes key events that happen to men in service, and after. We call this “longitudinal” data in our analyses.

- The Death Notifications are a memorial to those who fell in service, and tell us something about men’s post-war lives. Ultimately the research team want to study how men’s lives and health before and during the war influenced how long they lived.

So the Attestations are like a survey of men before their lives were changed by the war. New Zealand burned its census records after the results were published. While family historians and social scientists have used the censuses in Canada, Britain, Scandinavia, and the United States to study social life in the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, New Zealanders can’t do that. The military attestations are like a census of 10% of the New Zealand population in the early twentieth century, telling us about men’s occupations and birthplaces and education.

Because the attestations are cross-sectional, they are a little easier for the research team to analyze. We don’t need to order a series of events like we do on the Statement of Services or the History Sheet. The Attestations are also mercifully free of the sticky notes that were a design challenge for the History Sheets.

But there was a design challenge with the attestations. The form changed significantly over the course of the war. The research team has a database of 23,000 men from World War I , so we selected two attestation dates from each month of the war. We looked at the questions asked in each month, and found there were more than 30 different versions of the form. It’s really hard to predict what will be on each form! That’s where you, the citizen scientists of Measuring the ANZACs come in. You have to recognize what’s on the form, match it to the questions we’re expecting, and draw the boxes for transcription.

A final design challenge with the attestations was that some questions are conditional or multi-part. They ask, for example, “Have you served in the military before”. If you have they sometimes ask, what branch, and how were you discharged? Across the various versions of the form we have seen two, three and four part questions. They’re the hardest to recognize.

With that background, lets look at how we identify an attestation and then mark it.

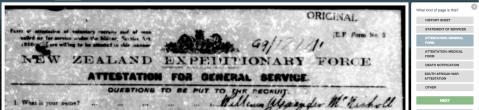

Identifying an attestation

One way to identify an attestation is that it says so right up the top! A lot of the forms are also labeled E.F. Form No. 2 (E.F. stands for Expeditionary Force). Many of these forms will appear to be of poor quality. The original paper copies were microfilmed in the the 1960s, and some of the original destroyed for some files. New paper copies were printed from the microfilm, and inserted into the files. These copies were then scanned in the 2000s to create the images used in Measuring the ANZACs. But you will see some original attestation forms, and in some files you’ll notice two versions. Please identify and mark both! It’s better to have too much information than not enough.

One way to identify an attestation is that it says so right up the top! A lot of the forms are also labeled E.F. Form No. 2 (E.F. stands for Expeditionary Force). Many of these forms will appear to be of poor quality. The original paper copies were microfilmed in the the 1960s, and some of the original destroyed for some files. New paper copies were printed from the microfilm, and inserted into the files. These copies were then scanned in the 2000s to create the images used in Measuring the ANZACs. But you will see some original attestation forms, and in some files you’ll notice two versions. Please identify and mark both! It’s better to have too much information than not enough.

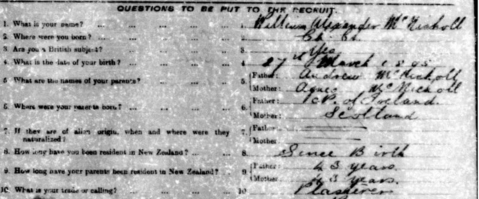

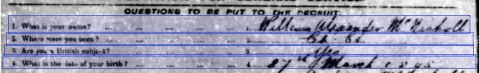

Another way to recognize the Attestation (General Form) is the initial sequence of questions which often starts with the recruits’ name, and questions about his birth date, birth place and next-of-kin. The questions about kin vary tremendously in form across the war.

Marking the attestation

The first thing you’ll be asked to identify is the serial number which is written in the header of the page. The location of this can vary tremendously. Sometimes it’s in a specified place and labeled serial number or regimental number. Other times it’s just written in the header. We’re asking you to transcribe this as a check that we’re getting the right serial numbers associated with the right person.

We then ask you to identify the various questions, with slightly different dialogs for the format of the question.

Here are some examples of one-part questions marked. Notice that the boxes can overlap a little

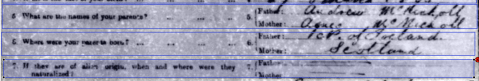

The next questions (below) are two part questions, asking the same thing about the recruits’ father and mother. These are quite obviously two part questions because they ask about two things, and there are two lines.

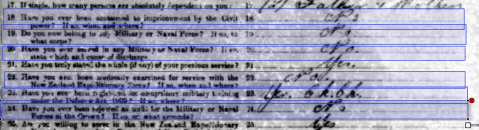

But there are more complicated two part question as seen in these examples

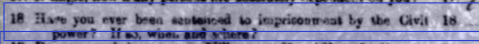

Lets take a closer look: The first question has the form “Did something happen”, and the second part has the form “If so, tell us more”

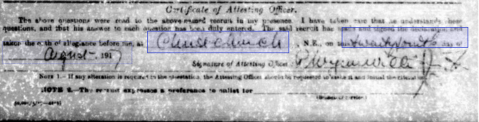

We go all the way down the page marking sections where there are questions or text, making sure to conclude with the date and place of attestation, which is at the bottom (Christchurch, 24th day of August 1917 in this example, it’s hard to read).

How does this work when we get to transcription?

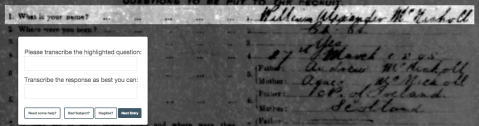

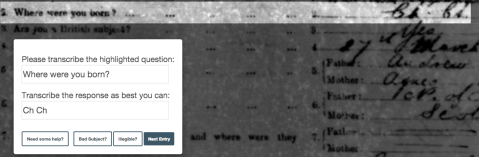

Because there are so many different forms of the question we, unfortunately, have to solicit your help in transcribing the questions too.

Luckily the question text is printed, and easier to read! You don’t need to transcribe the number of the question.

Here’s the next entry for which we’re doing the same thing. Note that we’ve transcribed the birthplace here exactly as written “Ch Ch”. We know this is Christchurch, and we’ll be able to classify it as such without you needing to correct the abbreviation.

If you think a mark has been placed around the wrong place on the page you can select “bad subject”. Sometimes in marking people draw erroneous boxes. This is our way of handling them.

If you can’t read the text please mark “Illegible.” This is more helpful than a bad guess. If it’s marked Illegible it’ll be offered up for someone else to transcribe. This is the power of the crowd! We try to distribute the work to someone who can do it.

In our next tutorial we’ll turn the page again, and look at the medical part of the attestation. This is a really important part of the researchers’ data collection, and it turns out to be one of the simplest pages to mark and transcribe. The information and layout didn’t change much, and the writing is often much better.

Happy marking and transcribing, and thanks for Measuring the ANZACs with us!