Measuring the ANZACs Tutorial 3: Marking History Sheets

In our last blog post we covered the basics of Marking. Marking is fundamental to capturing the information off the personnel files, as it structures the information that will be transcribed into “fields” or “variables.”

You can think of the fields as equivalent to columns in a spreadsheet. Every row describes a person, and every column has the same kind of information in it: a name, a birth date, a birth place, etc … The structure of the data gets a little more complicated than that because some things can appear multiple times for the same person. For example, people could get sick, or be wounded multiple times. This means the data is hierarchical (a future post will look at how we process the data for research).

The History Sheets (see the Field Guide) are a vital part of our research because they describe the “exposure” that soldiers had to sickness, wounds, and battle. They are also vital in making the Measuring the ANZACs database a platform for other researchers to do further research in the personnel files. With more than 4 million pages for 140,000 personnel files it’s unrealistic to think we can transcribe all the information (but if every New Zealander transcribed three pages we’d be done …) in a short time. The History Sheets summarize the key events that happened to men, and will help us create a highly refined index of the men who served according to many different criteria including where people served, when they served, where their hometown was, whether they were injured, and who their next of kin were. The importance of an index like this might be appreciated with this example: at the moment we have no way of identifying the personnel files of those who served at Gallipoli.

In short, the History Sheets are valuable because they summarize so much about a person’s service. This will let researchers, including you (!), delve into the stories in other parts of the file. The History Sheets are like a menu to what else we might find in a man’s file.

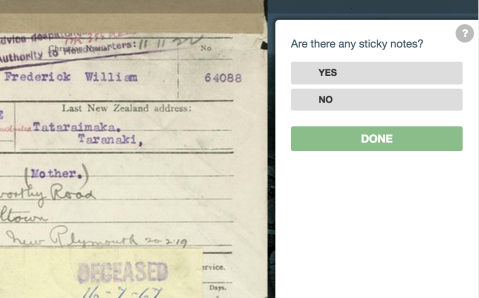

As we noted in one of our first blog posts, the History Sheets were working documents for the administration of an army and a welfare system for returned soldiers (veterans). Their history as working documents is reflected in the “sticky notes” that are affixed to many of them, particularly ones that record a long history of service. This was a particular challenge in designing the interface you are using to mark and transcribe.

As we noted in an earlier post the way Archives New Zealand dealt with the challenge of the sticky notes was to scan the same page multiple times to capture the information on the sticky note, and what was hidden below. It is very important that you classify all views of the same page as a History Sheet, and mark the fields on it, even if there is some duplication.

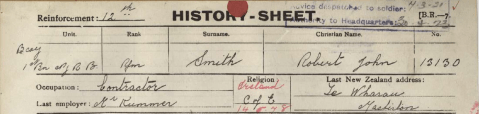

Identifying a History Sheet: Most of the time you can identify a History Sheet because it says so at the top of the page.

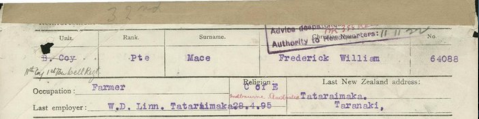

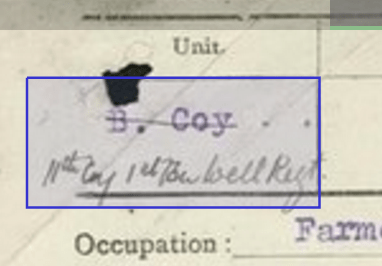

But not always … Because these were working files, and the History Sheet often appeared at the top of the file it was more likely than other parts of the file to be covered up with tape, like this …

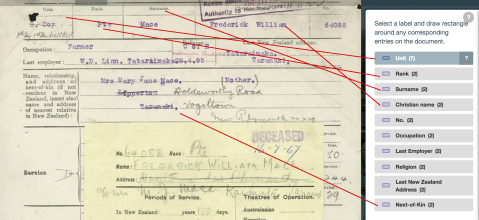

So you need to be able to identify a History Sheet from the key elements that nearly* always appear at the head of the page: Unit, Rank, Surname, First Name, No., Occupation, Last Employer, Religion, and Last New Zealand address. These are key pieces of summary information that were often taken from the attestation. Another way of identifying a History Sheet is that they are often a beige or tan color. (* Citizen scientists have seen other examples of the History Sheet. If you’re unsure, click on “Discuss this personnel record” in the lower right corner of your screen, and find out from the researchers, moderators and other citizen scientists over in Talk.)

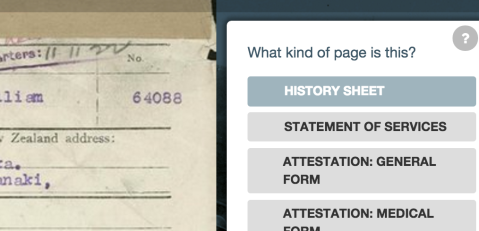

1. Identify the page as a History Sheet.

In the Mark workflow, you’ll click on History Sheet, and then click “Next”

2. Tell us if there are any sticky notes on the page.

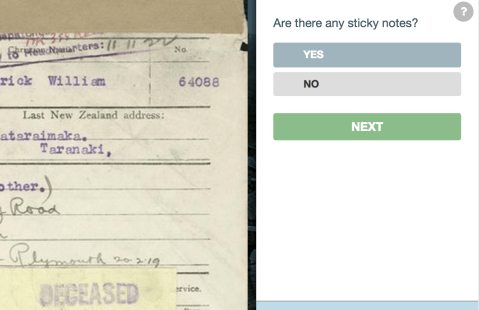

After you’ve identified this as a sticky note you’ll be asked are there any sticky notes, and in this case we click “Yes”.

and then click “Next”

3. Now you’re onto the Marking of the individual fields

There are a lot of fields on the History Sheet, and it presents you with the options in the order we expect to see them.

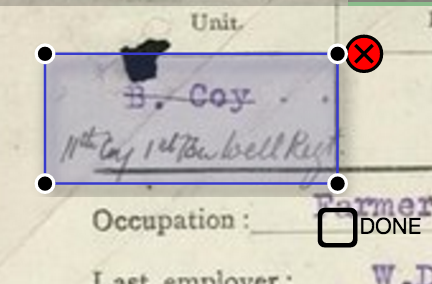

Select a field in the list on the right, and find the corresponding space on the form where the answer to that question is written. Draw a box around the answer, and when you’re satisfied with the box, click “Done”.

Now your box will show up ready to be transcribed by you or someone else from our great force of citizen scientists.

You do the same thing for all the other fields for which the answers are visible on this page.

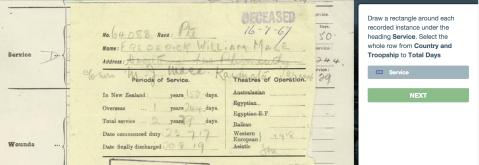

Scrolling down the page you’ll notice that the “question” for Service is visible, but the “answers” are hidden by the Sticky Note. Don’t mark any fields on the Sticky Note, or fields which are obscured by the Sticky Note.

If you want to see what the next page looks like you can navigate to the next page by using the page navigation tool on the left side of the screen. Click on the this icon to see the next pages.

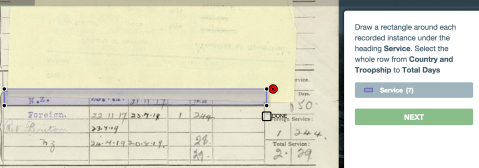

4. Marking Service, Wounds, and Sickness rows

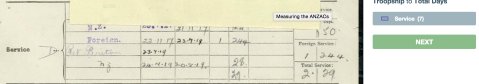

Our next view of the same page shows what’s under the Sticky Note. Here we come to the information that summarizes a man’s service. The key thing about marking this section is that you make multiple marks, one for each row in which there is information.

Note the instructions about which parts of the row to select. The next three screen shots show us doing the first three rows here. You’ll note that the boxes can overlap, because the writing sometimes spilled over the lines.

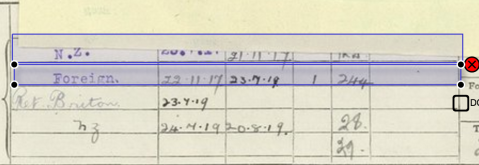

1. First row of service marked

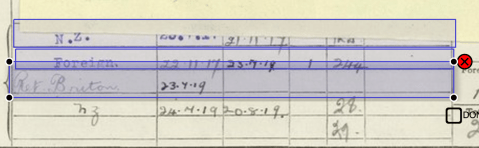

2. Second row marked

3. Third row marked, notice how it overlaps the second row

These same principles apply to marking Wounds and Sickness, which could happen multiple times to people. Mark each separate instance with a different box. This is very important, because it helps us create a count of the number of “events” that happened to people. Eventually we will use the separate information from each row to compile an electronic history of each man’s service. We will be able to calculate things like how long a man was sick during the war, and how long he was suffering from wounds.

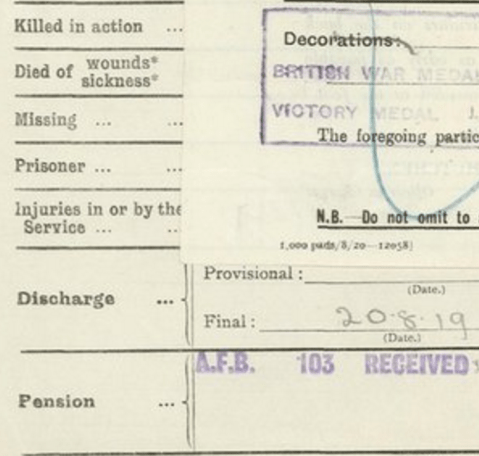

5. End of service

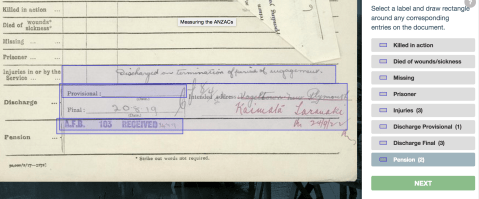

Finally we come to some fields that often describe the end of a man’s service in various ways: death, missing in action, being taken prisoner, and discharge; and some information on pensions.

Some of this is obscured by another sticky note, so lets hop over to the final version of this page to see what’s there. We have some information in the “Injuries row”, some information on a final discharge date, and an entry in the pension row.

For the discharge fields we are most interested in the dates of discharge. Here you’ll see that he leaves on 20.8.19 (20 August 1919). We’ve noticed some people have included the intended address in these fields, and that’s OK. It’s quite easy to identify what is an address, and what is a date.

And then we’re done with marking this page. You can click on “Transcribe this page now!” if you want to transcribe, discuss it in Talk, or share your find on social media.

Or if you just click Next you’ll move to another page for marking.

This covers the basics of marking a History Sheet, and will hopefully get you through most of them. Some are more complicated, so join the conversation in Talk by clicking “Discuss this personnel record” if you have any questions to ask about a particular page. All questions are good questions, and we have a great force of researchers and citizen scientists who want to help. Thanks for joining the forces to Measure the ANZACs!

(Here’s a link to the file we were using for the screen shots)

Trackbacks / Pingbacks