We are on the move

With some (much, much less) of the trepidation that must have been in the minds of soldiers going over the top in World War I, we are about to move to our new site on April 15. You should find that our URL — http://www.measuringtheanzacs.org/ — will redirect to the new site. As with all the best laid plans, we don’t know quite how this will go …

We have rebuilt the workflow on the new Zooniverse software that is more stable, and continues to be supported. There are some significant changes, but we hope that you will quickly get used to the site.

At first we have just two tasks available: sorting pages, and transcribing History Sheets. These are performed separately, rather than in one integrated workflow. We think that as the database got very large, the integrated workflow was probably slowing down the site.

Unlike the previous site, we are unable to offer support for browsing entire files. This was a feature of our previous Scribe software, but it is not built into the Panoptes “software stack.”

Once we have seen that our History Sheet transcription workflows are working, we will release work flows for the other key pages: Attestations, Medical Attestations, Statements of Service, and Death Notifications.

The initial group of soldiers whose files are represented on the site are a special group. They are men who died during, or shortly after, the war and are remembered on war memorials in the Far North, including Kaitaia.

We were honored last year to work with historian Kaye Dragicevich and contribute biographies of some of these soldiers to a book about them that will be published soon. As part of this collaboration, University of Minnesota Learning Abroad students working with Measuring the ANZACs researcher Evan Roberts visited Kaitaia and presented their biographies.

There are 2608 pages of files on 120 men represented on the site, and we hope that you will appreciate knowing the special history of this collaboration and what linked these men.

Our new site design will make it much easier for us to collaborate with you, and use Measuring the ANZACs as a platform for quickly transcribing the files of particular groups. If you can provide us with the list of men or women whose files you want transcribed, we can arrange for this data to be included in different batches of uploads. Please be in touch with us at measuringanzacs@umn.edu to discuss the possibilities of collaboration.

A new design and new software

If you’ve been doing any work on the Measuring the ANZACs site, you’ll know it’s been sluggish lately. We know too, and we’re sorry. So we’re re-designing on a new underlying software platform.

Despite the problems, we are going to leave the current site up. What we’ve seen is that if you use it by marking a page, and then selecting “Transcribe this page”, there is some sluggishness; but not nearly as bad as when one goes to Transcribe. There are a class of students in Wellington who might be able to use it in this way later in June 2018. Leaving it up isn’t going to delay the new site, as the underlying software for the project is not being actively maintained.

When we launch the new site, the design will change. The experience of being in the archive flipping through a set of pages will be gone. The first task will be to sort pages. We’ve noticed that we’re not getting enough people hitting the medical attestations, which was really our motivation for the project! We live and learn. To increase the chances people hit the pages we want to see, we’ll be presenting pages in a more random order. This has its pros and cons, we recognize.

Once 3 people have voted that a page falls into a particular category (History, Statement of Services, Attestation, Medical Attestation) it will be passed along to a different workflow to transcribe that kind of page. We think we know all the varied questions on the Attestation now, and can hopefully make the experience there more similar to the other pages, where you select pre-determined questions; rather than typing both question and answer.

The workflows for transcribing each page will be somewhat separate, so at first we’ll launch transcription for the simplest pages. In other words, the Attestations will be identified but may not be immediately available to Transcribe for a period of time. They’ll come eventually.

Another change will be that transcription of each question will likely take place immediately after you’ve selected the box for it. We hope this will mean fewer pages marked up and not finished transcribing.

Designing a citizen science site for transcription of complex documents has a lot of tradeoffs, and we intend the ironic statement that we’re fighting the last war. We’re trying to correct problems from the current site, but can’t fully anticipate the downsides of the new layout. We’ll be active on social media and here to get the word out that the site has re-launched. Thanks to our thousands of transcribers who have helped us gather a significant amount of data, and learn about the challenges of crowd-sourcing the transcription of complex social data.

An overdue Measuring the ANZACs update

It has been too long since we shared a progress update with our loyal transcribing forces. Thank you, as always, for the work that you are doing with us to build towards a complete transcription of New Zealand’s World War I soldiers.

Last year we reported that we had carried out initial assessments of transcription quality, and built our procedures for key fields to allow us to piece together a coherent record of one soldier’s life. The challenge, evident on reflection, is that even if all three transcriptions we have on a person are very similar (even identical) we have to develop a process for saying that. It’s the transcriptions that are just different, but basically saying the same thing that need work to reconcile.

With those processes built, we have begun research projects to scope what we can do with the data. As you know, our goal is to build a very large datasets of tens of thousands of soldier to measure height and weight and health. At the moment we don’t have tens of thousands of complete records (so please keep transcribing, and tell your friends to join in!) so we are taking advantage of the depth of information on a smaller number of records to explore other aspects of soldiers’ lives.

One particularly interesting aspect that you, our citizen transcribers have noticed, is the misconduct citations. Working in a Sociology department with great criminologists, Evan Roberts has recruited students to analyze the misconduct citations. As our transcribers will know, what we ask with misconduct citations is that you identify whether or not there’s a citation. So we’ve been checking how accurate those Yes/No answers are. Mostly pretty good. We think a few people are led astray by our instructions that you answer yes if there’s “anything below” the heading Conduct Sheet. Literally speaking, the marriage and children information is below the heading, but we ask people to identify Marriage and Children information in a separate set of marking and transcription steps.

We’ve identified that offenses fall into about six key categories:

- Absence without leave, or overstaying leave

- Drunkenness

- Insubordination or disrespect

- Disobeying orders

- Theft or damage of property

- Other offenses

Punishments came in four general types

- Deprivation of pay

- Deprivation of liberties (eg. confined to barracks)

- Reprimands from officers

- Physical restraint (Field Punishments #1 and #2)

A fascinating aspect of the relationship between offenses and punishment is what happens if someone is drunk as well as committing other offences? Does the drunkenness intensify the punishment, because it’s another thing done wrong, or does the drunkenness, in a sense, excuse and explain why someone damaged property or was out late? Our initial analyses suggest that the excuse and explanation perspective was more common. We can also see through this analysis, paired with the data you have transcribed how misconduct fit into careers. Soldiers who committed misconduct while still in the lower ranks seemed to have a harder time getting promoted as one would expect. However, soldiers already promoted to the lower officer ranks and then committing misconduct seemed to have innoculated themselves from getting demoted. The initial promotion showed they were worthy, and minor misconduct did not hold them back.

A new and re-designed site: We are excited to share with you plans for a new and re-designed site. We will be introducing what we hope is a streamlined process. One thing that will likely be lost in this new design is the ability to browse through all 30 or more pages of a long file. But by doing this, we hope that people will get all the way through shorter segments of files, of no more than 10 pages.

The re-design will start with a task sequence that just asks people to sort pages into our four types, plus “Other”. Once a page has been voted into a page type, it will be available for marking and transcription. We are going to try and take advantage of your work transcribing all the question test for the attestations by having pre-specified items on both pages of the attestation as well, now that we know all the questions. There will still be an option to transcribe a question and answer, if necessary.

We hope that the new site may be up and running by the end of summer, and we’ll let our loyal transcribers help us out with testing. The new site will allow us to collaborate better with other researchers who want to upload and transcribe a particular set of men’s files. Currently this is clunky at best. Stay tuned, tell your friends to join us, and please keep transcribing!

Rare but routine (or vice versa)

As you know we’re not transcribing all the documents in the Measuring the ANZACs files. We’re concentrating on the pages that give our research group, and other researchers including family historians, the best return on our collective time (thank you for transcribing, we really appreciate it).

The documents we’re transcribing are routine, they’re found in nearly every file. Excepting the South African files, which have a structure all of their own, the most common set of documents in the files are the History Sheets which come in two forms.

This is the most common

but you also see ones like this

The numbering suggests that the top version is the later and more widely used one.

In the same way we have two versions of the Statement of Services, one like this (the later version)

and another like this from earlier in the war

Nearly all files have an attestation (and sometimes two copies), but they don’t tend to be found in officers and nurses files.

Active casualty forms are found in lots of files because so many of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force were killed or wounded (60% if you believe the contemporary calculations and reports)

What’s interesting to us are the forms that seem routine, but don’t show up in many files.

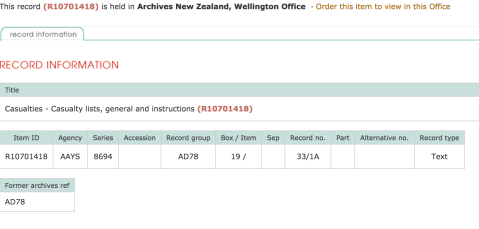

One of our transcribing forces, 141Dial34 who’s become a community moderator found this document recently. It’s a report on casualties issued in October 1916. Unremarkable in many ways, but look at the second row. It’s Casualty List No. 422. Lists are just ordinal, and so could start at any number. But typically people who are not mathematicians start lists at 1.

Why don’t we see these lists in more files? One reason would be that they’re duplicative when they appear in individual files. Our partners at Archives New Zealand appear to have a collection of more of these lists.  Here’s another example just posted today. It’s an age declaration. We know that about 10% of the men who tried to enlist were “adjusting” their, typically two years upwards. This looks like a mimeographed piece of text (the purple lettering is a giveaway), so this was probably done multiple times. Why don’t we see more of them in the files?

Here’s another example just posted today. It’s an age declaration. We know that about 10% of the men who tried to enlist were “adjusting” their, typically two years upwards. This looks like a mimeographed piece of text (the purple lettering is a giveaway), so this was probably done multiple times. Why don’t we see more of them in the files?

If you’ve worked with archives you’ll know that not everything is saved. Some pieces of paper are thrown out because they’re routine, or they are seen to have little value. The survival of some of these documents in some files hints at the culling that’s occurred, and what might have been the full record.

If you find something different, use the Discuss this personnel record link to bring it to Talk. It builds our Measuring the ANZACs community, introduces you to others who are transcribing, and helps research. We’ve started looking at the POWs after some examples were brought to our attention on Talk. We also love to share your finds with a wider audience on social media. Your chance at fame.

As always, thanks for all your contributions to the Measuring the ANZACs community and effort.

Evan Roberts (eroberts [at] umn dot edu)

Who’s doing all the transcriptions?

We reported last week that we were making great(er) progress with nearly three quarters of a million fields transcribed after 16 months. Another thing that’s interesting is to look at who is doing the work?

An important thing to know is that if you’re not logged in we just record you as an anonymous user. Just over 100,000 of our transcriptions were like that. We suspect there are some repeat visitors in there, and we hope you’ll register!

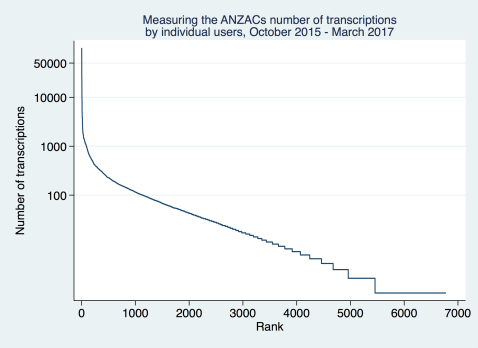

Like a lot of citizen science projects a lot of the work is being done by a small number of people. We had 6,670 registered users on the site, and just 80 people did more than half the work; starting with the top transcriber with 60,000 fields transcribed. In case this sounds unreasonable it’s the equivalent of someone who joined us when we launched and has transcribed one soldier a day … It’s great but might be only taking them 15-30 minutes a day. We need dozens more like them!

On the other end of the scale there are more than 1000 registered users who did just one transcription. Most likely—since they’re registered—they’ve come over from other Zooniverse projects, and didn’t stick around.

You can visualize this in a couple of ways. Because the numbers are so skewed we take logarithms (remember your high school or college mathematics!) to make the graphs more legible.

This is not at all unusual to Measuring the ANZACs. Citizen science participation follows a “power law” and our project is different from galaxies and penguins just in its content.

Evan Roberts (eroberts [at] umn dot edu)

We’re making even quicker progress!

In our first year we had 545,000 fields transcribed (a field is a single box that you enter text into). Just four months later we received another batch of data, and we’ve now got 761,165 fields transcribed.

Lets put that in perspective — 40% more data has been transcribed in just over 4 months, so we’re doing even more than we were achieving in the last few months of 2016.

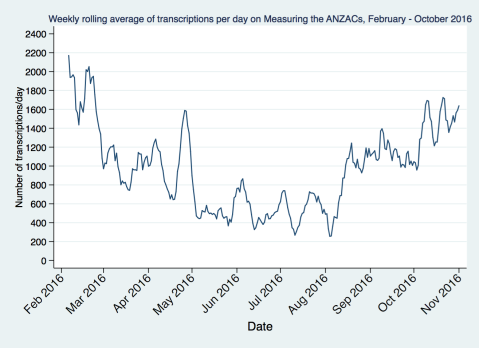

One of the best ways to see this is look at the weekly rolling average of daily transcriptions. This helps smooth out the day-to-day variation but also see short run changes and trends. These help us keep an eye on how we’re engaging the community. If you’re not coming back to help tell the stories of these soldier’s that’s a worry!

You can see that we kept up the steady pace of transcriptions we’d started achieving from August 2016, and what’s really encouraging is that people took a break for Christmas and then came right back to it during January. This is great, and gives us some quantitative evidence that we’re building a good community of people transcribing with us. We had a class working on the site in early February (and we’ve taken out the spike right before they had an assignment due!) which has helped us out.

On average we’re getting through 1600 fields transcribed a day. This is great, and is the equivalent of about 6 soldiers’ files being completed each day. One thing we’ve noticed is that the History Sheets, which appear first, are the most worked over. We really need people to work through a whole file if they can. Eventually History Sheets will be retired when everything has been marked once and transcribed three times. But with the incredible levels of accuracy you’re achieving we can make great use of the first version of a transcription. So the more our transcribing forces can spread their effort through a file the better!

Thanks for all that you do! Lets keep going and the more you can recruit others to join the Measuring the ANZACs forces the quicker we’ll complete our journey.

Service dates tell us a lot.

I’ve been using the Measuring the ANZACs platform in my Sociology of Health and Illness class this semester at the University of Minnesota. Teaching young adults in the Midwest why soldiers’ records from early twentieth century New Zealand are relevant to modern understanding of health and illness has helped me think more deeply about the material we’re working with.

For example, a big research question in the social scientific study of health is how do stress and trauma (different, but related things) affect our lives? How do our social connections help us survive bad things. In the long term as we assemble more and more individual records we’ll also have data on the units men were in, and can investigate the experience of what happened to men who served together.

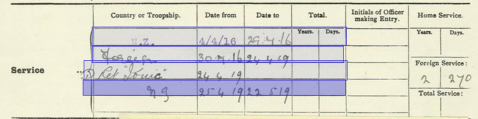

For now, we can do a lot with simple information. Take service dates which are summarized on the History Sheet (check out the Field Guide if you’re new to the Measuring the ANZACs forces). We can get an amazing amount of useful information about what affected men’s health and life from these four lines.

What colour was soldiers’ hair? Find out as we test our aggregation workflows

As we process our first large batch of data (thank you for the great progress made!) we’re interested in evaluating the accuracy of the work, and testing our workflows for aggregating multiple transcriptions on the same person into one. We began by looking at data for which we have verified entries—the name and the serial number.

Now we’re moving onto looking at how we aggregate text that takes on categorical values. A good rule of thumb in data processing is to start by looking at simple things first. In this case, simple is a question that doesn’t have a lot of possible answers. Hair color is an interesting one, and perhaps the results will be of interest. What color hair did New Zealand soldiers have?!

We were again encouraged by the apparent accuracy of the data. Of 3,216 transcriptions of hair color just 15 were not a hair color. Interestingly they were a religious profession which is beside it on the form. We can probably find the hair color in the entry for religion for these men. Transposition of entries from a known place is a problem, but a workable one. Of course, we should emphasize that an error rate of < 0.5% is really good.

.

.

The example here also shows another funny issue. A couple of people transcribed this as “light possum”, and we can see why! Context suggests that it is “light brown”, and the majority of transcribers recorded it that way. But since we use “flaxen” for blonde, why not use “possum” for grey hair.

To the data! We find that New Zealanders were a dark haired people, with 80% of the soldiers being described as having “brown,” “black,” or “dark” hair. The “fair” including flaxen were a small minority.

| Hair colo(u)r | Frequency | Percent | Cum. Pct. |

| Brown | 414 | 57.50 | 57.50 |

| Black | 97 | 13.47 | 70.97 |

| Fair | 80 | 11.11 | 82.08 |

| Dark | 72 | 10.00 | 92.08 |

| Other | 22 | 3.06 | 95.14 |

| Red or auburn | 21 | 2.92 | 98.06 |

| Grey | 14 | 1.94 | 100.00 |

Working through this data was a useful trial for our aggregation of more complicated fields. We hope you found it interesting, and look forward to sharing more results with you as we continue our research. Thanks for all your hard work, and lets keep transcribing!

Evan Roberts for the Measuring the ANZACs Research Team (@evanrobertsnz).

Citizen science produces highly accurate transcriptions

We reported last week that we were analyzing the 545,000 fields transcribed from our first year of collaborating with our citizen army to tell the stories of and measure the ANZACs. Among the first things we’re looking at is this question: how accurate are citizen transcriptions. If you’re reading this blog post you’re already among the most engaged volunteers, and so you will be thinking “I take a great deal of care with my transcriptions!” However by having our project open to the world we trade off the benefit of openness for the cost of having some less experienced volunteers who may not read the instructions, or take as much care.

So our question is to measure the measurers: how accurate are they, are you?! We need to show you’re doing a job that’s as good as we could achieve with methods traditionally accepted in the academic world for transcribing this form of material, such as employing undergraduate or graduate students.

We have an amazing opportunity to measure the accuracy of transcription in Measuring the ANZACs because our index to the records includes three variables or fields: first name, surname, and serial number that we see in the data as well and that are being transcribed. So we have a “gold standard” we can compare to. In a lot of citizen science projects the research team have to hand validate a sample of their data (we’ll do a bit of that too).

We measure “similarity” between your transcriptions and the gold standard with a metric called a Jaro-Winkler score that measures the similarity of the “string” (a string is a sequence of letters or numbers). 1 represents complete accuracy, and 0 total inaccuracy.

But to make the scores more concrete consider that Charles and Cjarles have a similarity of 0.91; Gerry Reid and Henry Reid have a similarity of 0.8, and B and Benjamin have a similarity of 0.74. We can still make a lot of use of transcriptions that score as low as 0.7. Note in particular that “B” is an initial and this may just reflect that the paper had “B” instead of “Benjamin”. The transcription is accurate, but the original person writing it down should have put the full name.

Here’s what we found and presented at last week’s meetings of the Social Science History Association: Citizen scientists are creating highly accurate transcriptions on complex forms with messy handwriting. We have a little work to do to compare this to our previous data collection by graduate students, but on first impressions this is of a very high standard.

Transcription in citizen science is relatively new, and it is important to show that it produces acceptably accurate data. We think it has, and we look forward to now proceeding with our substantive analyses with a high degree of confidence in what we’re analyzing. As we continue with our validation of the data we’ll keep you informed. Now, lets get back to Measuring the ANZACs! Transcribe!

| Given name | Surname | Serial number | |

| Mean similarity score to truth (1 = absolute accuracy) | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Proportion absolutely accurate | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.89 |

| Proportion with similarity score > 0.9 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| Proportion with similarity score > 0.8 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Proportion with > 3 words in string (more likely problematic transcriptions) | 0.0029 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

Audacious and achievable: Progress towards our goals.

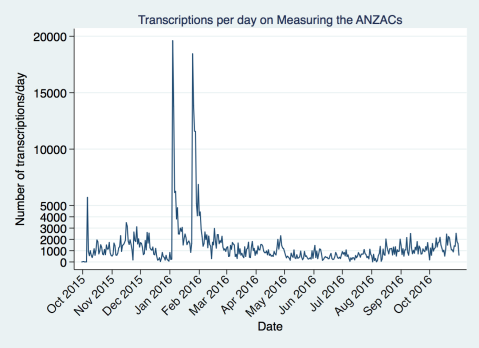

We got a batch of data out from the system recently, with more than half a million transcriptions of questions and answers.One of the automatically recorded pieces of data when you transcribe is the time and date.

Here is the raw data. We had a great opening week, and then in late 2015 we had some website problems. You can see how that affected our numbers, probably along with it being the holidays. What are the two huge jumps in January and February? Those are the days immediately following our interviews on TV One and TV Three. If we were on TV every night think how quickly we’d be done. Many hands do make light work!

As you can see from this graph there are some day-to-day fluctuations that make it harder to pick out the trend. It looks like the fluctuations are weekly, reflecting when people have more or less time (or faster internet at work?).

As you can see from this graph there are some day-to-day fluctuations that make it harder to pick out the trend. It looks like the fluctuations are weekly, reflecting when people have more or less time (or faster internet at work?).

There are some formal statistical tests for the “periodicity” of data, but for simplicity lets just look at the average over a week. We take the rolling average which allows us to get away from worrying about the audience for our project which is in multiple timezones. In effect our weekends are nearly three days because the New Zealand weekend starts when it’s still Friday in the United States (we know our community comes largely from the UK, US, and New Zealand).

Here’s what that looks like. We got a bit of a bump from the news coverage early in the year, and then things drifted down.

Lets focus then on the more normal part of the year to see what’s happening over time. We got a bit of a bump from some presentations and publicity in April/May 2016, and things slowed down a bit after that. We’re really gratified to see that since our presentations in Wellington in July 2016 there’s been a sustained growth over the last couple of months.

Is this enough to build a memorial and research database by the end of the centenary of World War I? Not yet! Every day we’re now completing the equivalent of about 2-3 files, depending on how many lines there are on the statement of services and History Sheets. By completing we mean that every field has been done three times.

How does this compare to other Zooniverse projects? Very well indeed. We’re not as popular as Galaxy Zoo or Snapshot Serengeti in classifications per day, but we’re around where Penguin Watch is, which is great. But our challenge is that each image (a page in a file) contains so much information. On each image we’re trying to get 5-30 pieces of information, whereas other projects have a smaller number of tasks per image. It’s just the nature of the material. So we need to keep going, and we need you, our force of transcribers to help us recruit more people. If you think there’s an analogy to the war and getting men to the front, you’re right. We need volunteers (and we need conscripts).

The goal is both audacious and achievable. Audacious because a complete transcription of the main pages of 140,541 files is a big task. Achievable because there are more than 3 million adults in New Zealand. If every high school student and their family adopted two soldiers and marked and transcribed their file we’d be done. If every one with an ancestor who served marked and transcribed one file we’d be done. Help us do that. Reach out now to people you know and share the goal with them. Thank you for a great foundational year, let’s keep going further and faster!